Consumer Update: FDA and Partners Working to Prevent Surgical Fires

On this page

- How Do The Fires Happen?

- A Daughter’s Story

- A Doctor’s Story

- Reducing the Risk

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is building a coalition of public and private healthcare organizations to prevent a medical error—the surgical fire.

A surgical fire is a fire that occurs in, on or around a patient undergoing a medical or surgical procedure. An estimated 550 to 650 surgical fires happen every year in U.S. operating rooms, according to the ECRI Institute, an organization that evaluates medical products and processes. Some fires cause disfiguring second- and third-degree burns. If the fire occurs in the patient's airway, it can be fatal.

Recently there have been news reports about two patients who received serious facial burns from surgical fires.

Karen Weiss, M.D., M.P.H., program director of the Safe Use Initiative in FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, notes that these fires are small in number compared to the millions of surgical procedures performed each year.

“They’re rare but when they happen, they can be devastating,” says Weiss. “And they’re preventable if the surgical team works together to reduce the risk of fires.”

FDA’s Preventing Surgical Fires Initiative is a collaborative effort to increase awareness of the risk of these fires and to encourage surgical personnel to work together to adopt practices that will prevent them from occurring. The initiative partners include associations that represent members of surgical teams, healthcare facilities, and healthcare engineering and patient safety organizations.

Two of the many partners are SurgicalFire.org, an organization dedicated to promoting awareness of surgical and operating room fires through education and collaboration, and Christiana Health Care System, headquartered in Wilmington, Del. Red flags went up there after two surgical fires occurred in one year.

How Do The Fires Happen?

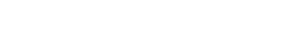

Fires can occur when the three elements of the “fire triangle” come together:

- Oxidizer: Gases used during surgery, such as oxygen and nitrous oxide, and room air

- Fuel: Flammable objects, including surgical drapes, alcohol-based skin preparations, airway tubing, and even the patient’s hair or body

- Heat: Tools such as electrosurgical (tissue-cutting) tools, lasers, fiber-optic lights and cables that can generate heat or sparks and cause a fire

Surgeries of the head, neck and upper chest pose a greater risk of fire, especially if the patient is receiving extra oxygen through a breathing mask or nasal tubing.

FDA regulates the drugs (such as oxygen and alcohol-based skin preparation agents) and devices (including electrosurgical tools, lasers and surgical drapes) that are components of the fire triangle and reviews product labeling to ensure that appropriate warnings about the risk of fire are included.

But, says Weiss, FDA’s regulatory authority is not enough to prevent these accidents from happening.

A Daughter’s Story

Cathy Reuter Lake became a patient advocate after her 72-year-old mother was burned in a surgical fire in 2002, sustaining second- and third-degree burns to her head, neck and upper airway. She was sedated for seven weeks because of the pain and suffered multiple infections before her death two years later.

Lake formed SurgicalFire.org to raise awareness in her mother’s memory. And Lake’s message to patients is: “If you’re going in for surgery, it’s your responsibility to ask questions.”

Questions patients could ask their healthcare provider include:

- What precautions are in place to protect patients from a fire?

- Is the staff trained in preventing, recognizing, and putting out surgical fires? Are they aware of the Preventing Surgical Fires Initiative?

- Are fire extinguishers readily available in the operating room?

“Patients need to have their own voice,” says Lake.

A Doctor’s Story

Kenneth Silverstein, M.D., chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology at Christiana Care Health System, says patients should “be aware that there is a risk and ask what steps are being done to prevent that.”

Surgical fires reached Silverstein’s radar in 2003 when two fires occurred that year at Christiana. The facility has since implemented a fire risk assessment with each surgical procedure.

Silverstein explains that before a surgery begins, the team evaluates the risk of fire, considering the oxygen source, the potential sources of ignition and the distance between the oxygen source and the surgical site. A risk score of 0 to 3 is assigned and that score is used to determine what safeguards are taken to protect the patient from surgical fire.

“The fix is incredibly inexpensive and it’s just the right thing to do,” says Silverstein. “The big challenge is to keep the potential risk for fire on everyone’s radar.”

Reducing the Risk

In addition to risk assessments, FDA is recommending other actions that healthcare professionals can take:

• Carefully evaluate if the patient needs extra oxygen.

• Prevent alcohol-based antiseptics from pooling during skin preparation.

• Ensure that alcohol-based antiseptics applied to the skin are completely dry before draping the patient.

• When not in use, place potential ignition sources (such as electrosurgical tools) in a holster and not on the patient or drapes.

• Ensure good communication among all members of the surgical team

• Practice fire drills so that everyone is aware of roles and responsibilities in the event of a surgical fire.

The Preventing Surgical Fires Initiative has educational materials and resources for healthcare professionals.

For patients, the site includes the Empowered Patient Coalition’s “10 Things Patients Should Know” about surgical fires, which outlines the risk factors.

Both patients and healthcare professionals are encouraged to report any experiences with surgical fires to MedWatch, FDA’s site for reporting adverse events (bad experiences with procedures and products).

This article appears on FDA's Consumer Updates page, which features the latest on all FDA-regulated products.

Dec. 9, 2011